Sadly, Joe passed away not long after he dictated this story to me. We were planning to do a series of stories starting with this and continuing through his training in Hawaii, his landing on Iwo Jima, his wounding, and his long convalescence. Those often told stories died with him. Semper Fi, Joe.

The March weather in San Diego is pretty easy to take for a guy from Illinois. My older brother, Chuck, a former DI and sergeant in the recruit depot’s guard detachment, pulled some strings so that I’ll be staying in San Diego for a little while longer to attend radio communication school. I joined the Marines last December to be a warrior and not a radioman, but Chuck must know what he’s doing, and the Corps really needs radiomen in this the second year of buildup, 1943. I’m so happy to be out of boot camp I’m willing to try anything to get into the fight, even learning Morse code and lugging a radio on my back.

I soon realize that radio communications is not my thing. All of this dit, dot, dit shit is driving me crazy and I’m not sure I’ll ever learn this stuff. What was Chuck thinking when he got me into this? Anyway, I earn my first liberty after one week of Comm. School and get to see a little of California with Chuck and his wife for the first time.

At Monday morning formation beginning my second week I learn that I’ll have to attend night classes with other “slow learners” until I catch up with the rest of the class. I’ve only been here one week and I’m already behind. I make a decision right then and there; I’m outta here as fast as my sorry ass will take me. How, I don’t know yet but it can’t be that hard. I’ve got to get out of here, this dit, dot, dit nonsense is not for me.

My mind is racing as we march across the grinder (parade ground) to our night school classroom. It doesn’t seem like you can flunk out of this school; they’ll just keep pounding this stuff into you until you finally get it. I could spend the entire war here trying to key in a three word message. The only way I can see to end this agony is to get kicked out for some disciplinary reason. Yeah, if I could get tossed in the brig for some petty offense they’ll boot me out of Comm. School, transfer me to an infantry unit and I can say goodbye to all of this dit, dot, dit bullshit.

Early in my first night class I take a break from memorizing Morse code long enough to start a letter to a friend back home. I just begin my letter when this piss-ant, little corporal looks over my shoulder and sees my letter. He reaches for my letter but I fight back yelling “You’ve got no business looking at this, this is private.” This asshole corporal won’t let up so I give him a little shove in the face with the palm of my hand. He staggers backwards outraged that I, a boot PFC, have laid a hand on him, an NCO. He storms out of the classroom and I never see him again. I just sit there for another hour or so until the class is over wondering what will happen next. Is this my ticket out of here?

The next morning shortly after reveille two MPs show up looking for Meyer. I yell, “Over here,” and they immediately arrest me and we march over “to see the man.” A couple of minutes later I’m standing at attention in front of the desk of this old, hawk-nosed, full-bird colonel. Remember now, I’m a 17 year old PFC with a total of three months in the Corps and I’ve never even spoken to an officer, let alone a bird colonel.

The colonel reads the complaint aloud and says, “Tough guy, huh?”

I respond with a feeble, “He had no business reading my letter.”

“You laid a hand on an NCO, five days bread and water. Take him away.”

The MPs march me over to the sick-bay (base hospital) where I’m given a quick going-over to see if I’ll survive five days on a protein-free diet. The doc gives me a thumbs-up as I’m sure he does every 17 year old Marine fresh out of boot camp. We leave sick-bay and head for the San Diego brig. The guys at the brig aren’t fun guys; they’re tough and cold and not the least bit friendly. Not at all like the MPs that have been marching me around.

They stuff me into a tiny dark cell with a bunk built into the wall and no where else to sit. I’m thinking I can put up with damn near anything for a measly five days. The thing that really sets military brigs (Marine brigs anyway) apart from civilian jails is all of the lines they’ve painted on the floors. Every time I come to a painted line I have to request permission to cross it from a chaser (prison guard) by screaming “Sir PFC Meyer requests permission to cross the yellow line.” The chaser will normally respond with “Go ahead shit-head” or some other more colorful response. So this is my drill for every minute I’m not in my dank little cell, yelling permission to cross their damn lines and being called obscene names.

I soon learn that bread and water means luke-warm water and all of the bread you can eat. It’s obvious they don’t want to starve me or break down all of the conditioning they’ve just put me through; they just want to punish me a little.

I whisper to the guy in the next cell over. If the chasers hear us they’ll be all over our asses. This guy must have connections to the outside because he smokes constantly and his cigarette smoke drifts annoyingly into my cell. One night he reaches through the bars and hands me an olive. Damn this little olive is good and it’s the only food I’ll have for five days besides bread and piss-warm water.

At the end of my five days two MPs pick me up at the brig and march me back to sick-bay where I’m surprised to find that I’ve gained a couple of pounds during my stay in the brig. It must have been that olive. As soon as I’m released I race to the mess hall afraid they may have quit serving breakfast. I’m in luck. I pile three pancakes on my tray but end up only eating a half of one. What did all of that bread and water do to my system?

The next morning when we’re getting ready to fall out for school a sergeant shows up looking for Meyer. I yell, “Sarge, what do I have to do to get out of here?”

“Get your gear together, there’s a bus leaving for Pendleton later today.”

I throw my gear into my sea bag as fast as I can. I’m not going to miss this bus. I don’t have any official orders, only the word of this sergeant, whoever he is, but I don’t care, I’m outta her!

The bus drops us off at Pendleton’s Camp San Onofre the home of the 26th Marine Regiment. I don’t have any orders and I’m clueless as what to do next. The bus driver points me to a company office at location 16B6. I tell the duty NCO that I’m fresh out of Comm. School, don’t have any orders and was just sent here by some bus driver. He doesn’t know what to do with me either so he points me to an empty bunk upstairs in the corner of the squad-bay.

The next morning I wake up in this unfamiliar place with a bunch of strange Marines wondering what the hell the Corps has in store for me today. Before long a lieutenant tracks me down and escorts me down to the company office. I soon learn that I’m bunking with Charlie Company, 1st Battalion, 26th Marines, 5th Marine Division. They tell me not to worry about my orders, the paperwork will catch up with me and I’ll be officially assigned soon, in the meantime, “Welcome aboard Marine.”

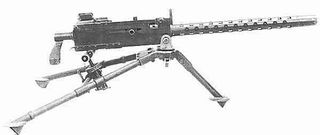

My new platoon sergeant tells me that machine gun training will start this afternoon in the barracks. He assigns me to Cpl. Joe Wilkinson’s machine gun squad as an assistant gunner. Joe is the squad leader and the gunner, the guy that gets to pull the trigger. Only one guy in a four-man squad gets to pull the trigger, the gunner. The other three lug ammo cans and tripods and feed the gun with ammo-belts. I decide right then that I’m going to be a gunner and not some ammo-belt feeding assistant.

After a few days out in the field I am promoted to gunner, a position I enjoy until the Japs silence my gun on Iwo Jima, but that’s a story for another day.

Often our lives are shaped and our destiny’s determined by some event that seemed petty or insignificant at the time. In my case the single event that transformed me from a suffering, incompetent radioman into a gung-ho, crack machine gunner … was my five days on bread and water.

Designed 1919

Produced 1919 – 1945

Weight 31 lb

Length 34.94 in

Barrel length 24 in

Cartridge .30-06 Springfield

Action Recoil-operated/short-recoil

operation

Rate of fire 400 – 600 rounds/min

Effective range 1,500 yd

Feed system 250 – round belt

Leave a comment