This beautiful green rock, this small chunk of copper ore, has been on my desk a long long time. It reminds me to never forget where I came from and of the epic events that had such a major impact on my life. It will be fifty years this summer since I was deported under armed guard from Bisbee, Arizona. But as I hold this rock it seems as if it were just last week.

This is my story.

Carlos Quintana

March 18, 1967

1917 – Bisbee, Arizona

I crouch down behind the nearly full minecart with my gloved hands over my ears. My knees are shaking as I pull them to my chest for protection. I wait in fear. I’m so scared. Why do they blast when we’re in the tunnel? Because we’re expendable, that’s why. We’re just dirty Mexicans.

A series of blasts go off further down the tunnel. The deafening explosions rattle the shaft. A gust of hot, dirty wind rushes by. The walls creak and groan as some rocks fall from overhead. One bounces off of my miner’s cap into my lap. I fear more will fall. I wait. Is it quiet? The explosions ring so loudly in my ears that I can’t tell. I stand shaking with fear and grab the minecart to steady myself. As I take a deep breath and reach for my pickaxe, Juan, my best friend, grabs my arm, grins, and yells in his Coahuila-accented Spanish, “Carbón, we got through another one, amigo. Someday this is all going to come down. Pray that we’re far from here when it happens.”

This is my fifth month deep in the Copper Queen mine, the pride of Bisbee, Arizona, and I’ve had my fill of mining for a living. If there were any way I could earn a living above ground, I’d jump at it.

Just as I shovel another load into the cart I hear the shift horn. Thank God, our shift is over. Juan’s smile beams through his dirty face as we hoist our tools over our shoulders and start the long trip up to the surface.

The summer sun is blinding as we come into daylight for the first time today. “Juan, why do we do this? There must be a better way to make a living than slaving away in a dark hole in the ground.”

“I’m sure there is, but this is the best we’ve got for now. Oh yeah, you can always go back to Mexico and join Pancho Villa’s defeated army. He’s nearly done and his soldiers are deserting him by the hundreds. Nah, I’d rather use a shovel and pickaxe, even for these pinché gringos, than die hiding in the hills like a bandit. That’s all there is for us in Mexico, war, starvation, and death.

The talk at diner is all about the miners union. Earlier this year the Industrial Workers of the World came here and began signing up miners to form the Metal Mine Workers Union No. 800. Last month the union presented a list of demands to the patrones at Phelps Dodge including an end to blasting while we are in the mines and a fixed wage of $6.00 a day. The company told the union where they could stick their demands. All the talk now is about a strike.

“Did you hear about that strike they had a couple of years ago in some other mine near here? All they accomplished was losing their wages and pissing the gringos off,” Juan tells the group.

“Yeah but this time we’ve got 1,300 miners in our union. Phelps Dodge will have to give in to our demands or we’ll shut ’em down,” someone yells. “We got those cabróns this time.”

A couple of days later everyone is excited. We’re going on strike to finally get those pinché gringos to listen to our concerns. We want a fair wage, and safer working conditions. They have to give it to us or we’ll put them out of business.

Early the next morning Juan nudges me, “Arriba, Carlos. The day has come. We are now on strike. No work for us today.”

“What do we do on strike?” I ask.

“I don’t know other than not go to work. We’ll just do what everybody else does. Now, get up, perezoso, we’ve got important strike stuff to do.”

We are milling around in front of our shack when a union organizer comes into camp. He waves his arms with excitement as he tells us that not only have the miners at Phelps Dodge gone on strike, but more than 3,000 miners, nearly all the mine workers in Bisbee are now on strike. The crowd cheers. “¡Viva la Unión! ¡Viva la Unión!”

Being on strike is pretty easy work. We have nothing to do. Most of the miners hang around town like vagrants. Some play cards in the park; others mingle with the locals and the few that can afford it, drink beer.

We never really know how the strike is going. Nobody tells us anything. I fear that we’re not making any progress. The union would be here bragging, if we were. A week or so later news comes down that the miners in another Arizona mining town, a town called Jerome, have struck Phelps Dodge and the company retaliated and severely punished the union organizers.

Everything was peaceful in Bisbee until early one morning we wake to a lot of screaming and shouting. Some gringos broke into our shack yelling and waving guns. They roust us off our mats and out in the street. The gringos all wear white armbands and yell out our names from their lists before marching us down the road like prisoners. The guards look as if they could shoot us at any minute. The distant sound of gunfire scares the hell out of me. Are these gringos going to shoot us?

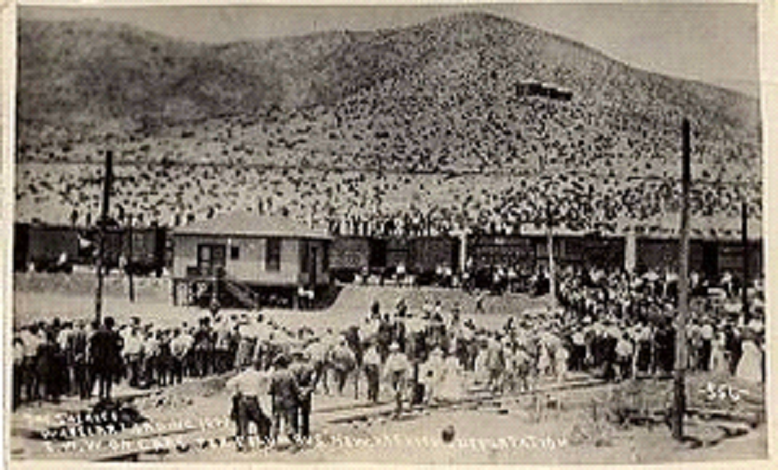

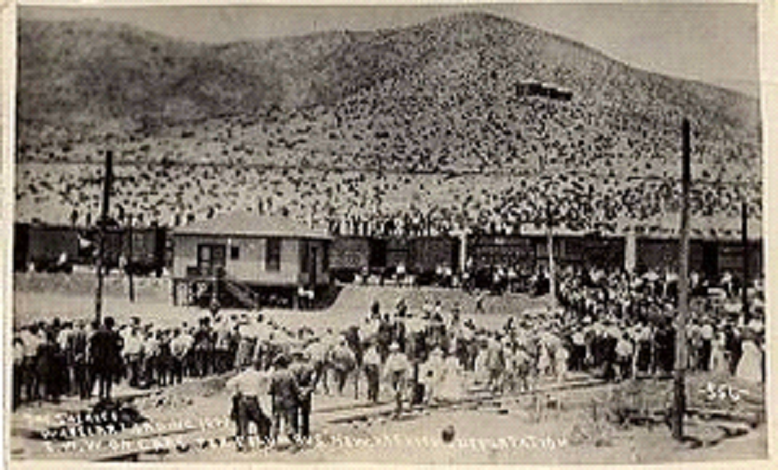

The sun is up by the time we join a lot of other miners in front of the Bisbee Post Office. There must be two thousand of us. Just as we get there we’re turned around and marched in a long line for two miles to the town ball field. The sheriff watches us closely as we come into the baseball field. He seems to be in charge.

We sit in the stands and wait until all of the striking miners are assembled. Many are down on the grass as the bleachers are soon filled. Some gringo announces in poor Spanish that we are all arrested, but if we denounce the union and go back to work we will be set free. A few hundred men raise their hands and are led away while the rest of us shout profanities and shake our fists. “¡Viva la Unión! ¡Viva la Unión!”

They leave us there in the sweltering July sun. A little before noon a thousand or so of us strikers are herded to the railroad station where we are ordered at gunpoint to board some filthy cattle cars. The car Juan and I are shoved into is covered ankle-deep in manure. It is hot and the odor of manure is overwhelming. About 50 of us are crammed into a tiny cattle car. Our car is packed so full that the door won’t close. The guards climb up on the top of the car to make sure nobody gets away. We are all crammed belly-to-belly when the train pulls out. “Where are they taking us,” I ask Juan.

“Maybe they are taking us into the desert to shoot us,” says this guy hanging on my right shoulder. The car is quiet. Deadly quiet.

Less than an hour later the train stops for water. We all get a drink before the train starts up again. We travel east all day and into the night. The stink of our bodies and our waste mixed with the manure make it almost impossible to breathe. Our legs scream in pain from standing for hours and hours in fixed positions. Many of the miners have passed out or fallen asleep standing. I can’t take it anymore. The pain. The stench. The thirst. All of these filthy bodies shoved together. Just as I’m ready to scream we pull into a town. Is this our destination? Our train just sits there. The guards drop to the ground and force us to stay inside. Hours later the guards climb back aboard and the train starts slowly back in the direction we have just come. In the early morning we finally get to where they are taking us. Nowhere.

We are so eager to get off of the train it doesn’t matter that we’re in a very small town in the middle of the desert. The guards hustle us out of the cars and away from the tracks. Those that can’t walk, crawl. The guards warn us that if we go back to Bisbee we’ll be shot. They leave us there, board the train, and take off. They’ve abandoned over a thousand men without food, water, or shelter in a town of less than a hundred people.

The sun comes up and we see we are at the foot of three peaks. Someone recognizes these mountains and shouts, “These are the Tres Hermanas. This must be Hermanas. We’re only twenty miles or so west of Columbus, New Mexico and maybe 200 miles from home.”

“Columbus, isn’t that the town Pancho Villa raided last year?” Someone yells out.

“Si, and they’re still pissed. We’re probably not welcome there today,” Another adds.

Everyone has an idea on what we should do. The loudest yell out their ideas. Let’s follow the tracks west to Columbus. No, we should stay here and wait for a train to come by. And, we’re less than 40 miles from Mexico, let’s go home.

I’m unsure what we should do when Juan nudges me and says, “We can maybe make Columbus without water if we go at night. It should be about a seven hour walk over pretty flat ground. We can do it, but … but I don’t know what we’re gonna find when we get to Columbus. They might shoot us on sight.”

Juan finds a little shade in a rocky arroyo and waves me over. It feels good to lie down, even on the sharp rocks, after standing so long. We both fall asleep without another word.

The arguments continue. What should we do? We’ll die out here without food and water. This little town can’t even support a fraction of our needs. We’ve got to go somewhere. The arguing is interrupted when someone shouts, “A TRAIN! A TRAIN!”

I see a bit of smoke on the western horizon. The crowd cheers as if our prayers have just been answered. The puff of smoke keeps getting closer. We all watch silently as the train pulls into the makeshift Hermanas station. Uniformed U.S. Army soldiers jump from the train and begin opening doors to the cars. Someone yells for us to give them a hand unloading boxes of food and water. The soldiers are not armed and seem friendly.

Before our thirsty crowd can make off with anything the soldiers organize us into lines and begin handing out the goods. Once we’ve eaten and drank our fill, a soldier announces that we are to board the train. They will escort us back to Columbus where we will be housed and fed.

This time we board the train on our own and ride the few miles in reasonable comfort. In Columbus we were greeted by even more soldiers. The lead us rather than march us to a huge tent camp where we were told to make ourselves at home.

The army takes far better care of us than Phelps Dodge ever did. We have army rations and comfortable cots with warm blankets. We are asked and willingly agree to work around the fort on various projects. I seem to always get stuck digging latrines.

After a couple weeks I learn that the army is building a large camp in Deming, a town 30 miles north of here. They need construction labor. Juan and I said goodbye to our fellow deportees and hitch a ride to Deming on an army truck. Camp Cody, just outside of Deming, is a huge construction project. We’re hired immediately as laborers. The work is hard, the hours long, the weather hot, but it beats mining. We work until the camp is nearly finished and troops start arriving. During our time there we helped build a hundred mess halls and over a thousand bath houses. Enough for 30,000 troops.

The U.S. had entered into the Great War in Europe earlier that year and the patriotic fever of the camp was catching. As soon as our work in Deming was done we enlisted in the U.S. Army and were sent east for training. My exploits in the Great War and the loss of my buddy, Juan, in France are stories for another day.

I often think that I should have thanked those armed vigilantes for herding me into that filthy cattle car and deporting me from my mining career. If left to our own choices Juan and I might still be mining copper, or more likely buried nearby in a pauper’s grave.

¡Viva la Unión!

Striking miners being forced into cattle cars in Bisbee, Arizona.

Author’s note: In the early hours of July 12th, 1917, 2,200 men wearing white armbands gathered in Bisbee, Arizona. At 6:30 am, on the sheriff’s command, these newly deputized vigilantes rushed through the desert mining town detaining all men thought to be union sympathizers. Hours later, 1,286 men were loaded onto manure-coated cattle cars to be transported 200 miles and 16 hours through the desert heat. The men were abandoned in the small town of Hermanas, New Mexico, without food, water, or shelter. The incident, known as the Bisbee Deportation, would be one of the largest vigilante actions against organized labor in American history.

Phelps Dodge, in collusion with the sheriff, had closed down all access to outside communications from Bisbee so it was some time before the story was reported. The Governor of New Mexico, in consultation with President Woodrow Wilson, provided temporary housing for the deportees. A presidential mediation commission investigated the actions, and in its final report, described the deportation as “wholly illegal and without authority in law, either State or Federal.” Nevertheless, no individual, company, or agency was ever convicted in connection with the deportations.